Wenn der Beltz em Loch hat -

stop es zu meine liebe Liese

Womit soll ich es zustopfen -

mit Stroh, meine liebe Liese

According to Angela Merkel, speaking in the German city of Mainz in mid February, European countries struggling with the fallout of the euro-area debt crisis have much to learn from East Germany’s experience with economic overhaul following the fall of the Berlin Wall. In the main she was speaking about the need for reform, something on which we can all agree. “At the beginning of the 21st century", she said, "Germany was the sick man of Europe and that we are where we are today also has to do with reforms we carried out in the past. That’s why we can say in Europe that change can lead to good.”

But there was one tiny little detail she forgot to mention. During the post unification period East Germany's population went into melt-down mode. New York Times Columnist Nicholas Kulish put it like this:

Unemployment in the former East Germany remains double what it is in the west, and in some regions the number of women between the ages of 20 and 30 has dropped by more than 30 percent. In all, roughly 1.7 million people have left the former East Germany since the fall of the Berlin Wall, around 12 percent of the population, a continuing process even in the few years before the economic crisis began to bite.Now this situation is quite serious, and needs a long term solution, but it is not as serious as what is currently happening to Latvia, or Bulgaria, or a number of the other former communist states. Unless, of course, the lesson Angela would like to draw our attention to is that East Germany managed to salvage something from what would otherwise be population wreckage by sneaking in under the shelter of another state, with a centralized system of support for pensions and health care. Somehow I doubt it, but perhaps this is what we need to think more about. The EU needs a pan European health and pension system, to distribute the burden equitably. This is the conclusion I reached during my last visit to Riga. It isn't just a Euro related issue, it is to do with having a unified labour market, with people able to move to where the jobs exist, and the pay is better. For years people complained about the absence of labour mobility in the EU. Now we have it, the flaw in the institutional infrastructure is obvious.

And the population decline is about to get much worse, as a result of a demographic time bomb known by the innocuous-sounding name “the kink,” which followed the end of Communism. The birth rate collapsed in the former East Germany in those early, uncertain years so completely that the drop is comparable only to times of war, according to Reiner Klingholz, director of the Berlin Institute for Population and Development. “For a number of years East Germans just stopped having children,” Dr. Klingholz said.

The newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung reported recently that although 14,000 young people would earn their high school diplomas this year in Saxony, only 7,500 would do so next year. Since 1989, about 2,000 schools have closed across the former East Germany because of a scarcity of children.

Young people are moving from the weak economies on the periphery to the comparatively stronger ones in the core, or out of an ever older EU altogether. This has the simple consequence that the deficit issues in the core are reduced, while those on the periphery only get worse as health and pension systems become ever less affordable. Meanwhile, more and more young people follow the lead of Gerard Depardieu and look for somewhere where there isn't such a high fiscal burden, preferably where the elderly dependency ratio isn't shooting up so fast.

I am sufficiently concerned about this issue, which I think ultimately endangers possibilities of economic recovery all along the periphery, to have created a dedicated facebook page, campaigning for one single issue - that the EU Commission and the IMF give a greater priority to trying to measure these flows, and understand their consequences. I am simply asking that they pressure EU member states to improve their statistics gathering, treat the issue as a priority, and identify an indicator to incorporate in the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure (MIP) Scoreboard. Really it doesn't matter whether you are in favour of austerity, or against it, feel more Keynesian than Austrian, or vice verse, all I am asking for is that this problem be taken more seriously, measured and studied.

Bulgaria The Classic Case?

Really there has been a before and after to the financial crisis, at least insofar as awareness of the demographic dimension is concerned. Really, before the onset of the crisis very few people really attached much importance to the question. Since the arrival of the European sovereign debt crisis, and the fiscal cliff debate in the United States, awareness has grown that population ageing probably will slow economic growth, and that previous expectations about levels of pension and health care provision may have been way too optimistic. The latest example of this has been Nobel Laureate Paul's Krugman's comments on how Japan's demographics may be influencing its growth rate. In a tellingly graphic expression he explains that the root of Japan's ailment might be that the country is suffering from a growing "shortage of Japanese".

Once you realise that population shortage may be a problem in Japan, you start wondering where else it might be one. And then, once you begin to look you start seeing the issue springing up like mushrooms all over the place. In Bulgaria for example.

According to the 2011 census, Bulgaria has lost no less than 582,000 people over the last ten years. In a country of 7.3 million inhabitants this is a big deal. Further, it has lost a total of 1.5 million of its population since 1985, a record in depopulation not just for the EU, but also by global standards. The country, which had a population of almost nine million in 1985, now has almost the same number of inhabitants as in 1945 after World war II. And, of course, the decline continues.

As well as shrinking the population is ageing. In 2001 16.8% of the population were over 65. Just 10 years later the equivalent figure had risen to 18.9%. Naturally this means the median population age is rising steadily. It is precisely part of my argument that this surge in median age over 40 has important consequences for saving and borrowing patterns at the aggregate level, patterns which have not yet been adequately measured and identified. Thus the macroeconomic dynamics of a country change. The impact of these changes has not yet been incorporated into the traditional models most analysts use in forecasting.

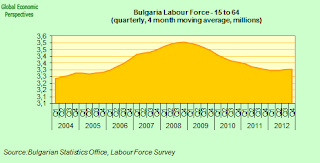

Naturally the workforce itself is in rapid decline.

The causes of Bulgaria's rapid ageing and shrinking population problem are twofold, low fertility and emigration. This is what makes the country look more like the old DDR and less like Japan. In fact Bulgaria's situation is an extreme case of what is happening in many East European countries, especially Romania and the Baltics. If you want another reference point, Ukraine would be in this group, but even worse, since it is even outside the EU.

Details of migrant numbers are scarce, and at best hedgy. The data we have is surely a significant underestimate, as the OECD pointed out in its latest country migration report:

Figures on declared emigration show an increase from 19 000 in 2009 to 27 700 in 2010. However, actual outflows are considered to be much greater, based on immigration statistics of th e main destination countries. Spain, the most important destination country in recent years, recorded 10 400 Bulgarians entering in 2010, 7% more than in 2009. Outflows of Bulgarian citizens from Spain also increased in 2010, to 7 600 from almost 5 000 in the previous year (+52%). The number of Bulgarians in Spain increased by 14 500 in 2010, and a further 13 000 in 2011. There are no consistent data for Greece, the second main destination of Bulgarian immigrants in recent years, but it seems that the stock increased less in 2010 than in previous years.

Remittances data gathered by the World Bank give the general picture. Basically there was a large surge following the severe crisis of the late 1990s, and since that time the level of payments has only weakened slightly, on the back of the severity of the crisis in the main destination countries.

Bulgaria is also pretty much what the old DDR would look like if it hadn't fused with Western Germany, namely it much more similar to Hungary than it is to Japan (in the sense I discussed in this post) as it has a significant negative balance on the net international investment position (though not as large as Hungary's), which means as well as being quite poor it is totally unprepared for rapid population ageing (since the text book way to sustain pension and health benefits in a context of increasingly weaker headling GDP growth is normally thought to be to draw down on overseas assets).

Bulgaria also bears comparison with Hungary for the way it has carried out a rapid correction on its external position. This is due largely to remittances and services exports, since the goods balance is still in deficit. But still, the turnround is impressive.

As elsewhere exports have performed very strongly.

But again to no real avail, since domestic demand is deflating so strongly that the economy struggles to find air...... and growth. In this sense it is hard to agree with the IMF Executive Directors when they state in their latest Public Information Notice, following conclusion of the Fund's 2012 Article IV consultation, they "broadly agreed that the currency board arrangement has served Bulgaria well". If allowing a country to drift towards long term melt-down is doing well, I would hate to see what something which they thought was an impediment would do! Some thing is rotten in the state of Denmark, and that something isn't being identified or dealt with.

Naturally part of the problem is that the flow of credit has dried up.

But the other part is surely the one Krugman identified in Japan, the growing shortage of Japanese (sorry, Bulgarians). It is hard to see how you can get serious retail sales growth in a population that is shrinking so rapidly. The end result is that the economy grew steadily into the global crisis, and subsequently has stagnated. This stagnation isn't simply conjunctural anymore, it has become structural, as the decline in domestic demand associated with ongoing deleveraging and population ageing and shrinkage precisely offsets the positive impact of all that export growth.

Not everyone is convinced, of course. The IMF expect the Bulgarian economy to return to a rate of growth of between 3% and 4% after 2014, but looking at the demographics and comparing it with what we are seeing elsewhere that seems pretty unrealistic. What is the expression Christine Lagarde would use? "Wishful thinking" perhaps?

In any event, in the short term the country looks set to significantly underperform any such rosy expectations. FocusEconomics Consensus Forecast panellists expect the economy to expand 1.4% this year. In 2014, the panel expects economic growth to reach the impressive rate of 2.4%.

Growing Political Discontent

Since Bulgaria is a small country, and a poor one to boot, most of the above had been going on virtually unnoticed by the rest of the world. Then last week the Bulgarian government suddenly resigned en bloc. The immediate cause of the crisis which lead to the resignation was the continuing rise in energy costs, a rise which was largely blamed on the Czech provider CEZ. To appease the street protestors the government has now initiated a procedure to revoke the company's licence, a move which has started to raise concerns about institutional protection in the country.

According to the report in Bloomberg:

Bulgaria’s State Financial Inspection Agency started a probe into CEZ’s Bulgarian units last year and submitted a report on Feb. 8, saying that CEZ ‘‘evaded requirements of the Law for Public Tenders,” the Energy and Economy Ministry in Sofia said on Feb. 18. The ministry asked the authority to conduct a similar investigation into the local units of Austria’s EVN AG and Prague-based Energo-Pro, it said. Bulgaria sold seven power distributors in 2005 to EON SE, CEZ and EVN before joining the European Union. EON sold its Bulgarian companies to Energo-Pro in 2011.Czech Prime Minister Petr Necas was not slow to respond:

“I regard the statements by Bulgarian officials about CEZ and other foreign companies as very non-standard and see the whole issue as highly politicized because of the approaching parliamentary elections,” Necas said. “I expect Bulgaria, as a member of the European Union, to stick to its international obligations, European law and its own laws on protection of foreign investments.”Naturally energy prices are not the only issue. The population is tiring of austerity, and living standards that don't rise even as unemployment does.

One symptom of this is that Bulgaria's government sacked Finance Minister Simeon Djankov at the start of last week. Djankov was closely identified with austerity policies, and it isn't hard to read his departure as an attempt to curry favour with voters in elections which are due this summer.

Having said that, the country's government debt at under 14% of GDP is incredibly low, so there is room for flexibility, if it wasn't populist flexibility. The real issue is that simply spending more this year, or next, won't fix the underlying problem, and that problem is unlikely to be addressed until it is recognized as a problem by the institutions responsible for economic policy formulation. As someone once said, de-nile is not only a river in Egypt.

This post first appeared on my Roubini Global Economonitor Blog "Don't Shoot The Messenger".

Postcript

According to wikipedia: "There's a Hole in My Bucket" (or "...in the Bucket") is a children's song, along the same lines as "Found a Peanut". The song is based on a dialogue about a leaky bucket between two characters, called Henry and Liza. The song describes a deadlock situation: Henry has got a leaky bucket, and Liza tells him to repair it. But to fix the leaky bucket, he needs straw. To cut the straw, he needs a knife. To sharpen the knife, he needs to wet the sharpening stone. To wet the stone, he needs water. However, when Henry asks how to get the water, Liza's answer is "in a bucket". It is implied that only one bucket is available — the leaky one, which, if it could carry water, would not need repairing in the first place.

The origin of this song seems to go back, oddly enough, to the German collection of songs known as the Bergliederbüchlein. Ironically Henry's Q&A with Liza fits the quandry facing the countries on Europe's periphery and their lack of constructive dialogue with their core peers about the roots of their problems to a tee.